Are you Writing Women’s Fiction?A Guide To Help You Determine If You’re Writing Women’s Fictionby Lidija Hilje, Author & Book Coach

Different sources define Women's Fiction differently. Some describe it as "fiction written by women, for women," or “an umbrella term for books that are marketed to women," or “books where the protagonist is struggling with 'feminine' flaws.” None of these definitions really gets at the heart of what WF is or how to differentiate it from other similar genres, also written mainly by and for women (like romance, for example).

Different Definitions of Women’s FictionGenre is a label that tells the audience what to expect from a story. This labeling can be based on different aspects of a story.Basic Genre Divisions

For instance:

We come to each of these genres expecting a particular kind of plot development and that the story will adhere to genre conventions.

Women’s Fiction as a GenreWomen's Fiction is defined as a story with a central theme of the protagonist's emotional journey.You might be thinking... hey, but don't most books have an emotional journey somewhere in there? Isn't that called the character arc? In many stories, there is a substantial character arc that supplements the plot, but in Women's Fiction, the focus of the story is the character arc; the change of the protagonist's worldview is what the story is all about. Women's Fiction Plot Just like thriller or romance novels have a specific formula to their plots that the readers have come to expect of those genres, so does Women's Fiction. At the beginning of the novel, the protagonist has a misbelief or character flaw, and the external events (plot) force them to change their misbelief/correct their character flaw by the end of the novel. If the crux of your story—what your story is really about—is the emotional journey of the protagonist, how they change or evolve over the course of your novel, then you're writing Women's Fiction even if...

How Women’s Fiction Intersects With Other GenresIn relation to the Women's Fiction genre, we often hear terms such as Book Club Fiction, Chick Lit, or Beach Reads. How do these categories relate to Women's Fiction?Think of Book Club Fiction, Chick Lit, and Beach Reads as attempts to segment the audience.

A work of Women's Fiction can be classified as any of these categories, but not every work of Women's Fiction is necessarily one of them.

Women's Fiction and Other GenresGenres can be classified in a multitude of ways:

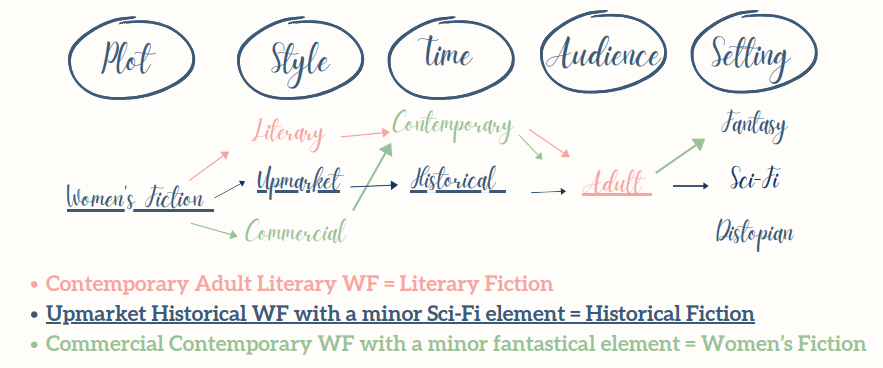

Literary Women’s Fiction Since these genres are defined by different criteria (Literary Fiction by style, Women’s Fiction by plot focus), they can intersect. A work of Literary Fiction that focuses on the protagonist's emotional journey will often lose the prefix “women’s fiction.” The same rule applies to Upmarket fiction. Examples of literary women’s fiction include Elizabeth Strout’s Oh, William! and Lily King’s Writers & Lovers. Historical Women’s Fiction Since these genres are defined by different criteria (Historical Fiction by time period, Women’s Fiction by plot focus), they can intersect. Not every historical novel is WF, but every WF novel set in a historical period is Historical Fiction. A work of Historical Fiction that focuses on the protagonist’s emotional journey will often lose the prefix “women’s fiction.” Examples of historical women’s fiction include Alka Joshi’s The Henna Artist and Clare Chambers’s Small Pleasures. Women’s Fiction with Romantic Elements... or Romance? Many romance protagonists have a strong emotional arc. After all, many of them have to overcome their own outdated worldview or character flaw to get together with their love interest. Meanwhile, many WF novels have romantic threads. So how can you tell if you’re writing women’s fiction with romantic elements or a straight-up romance? To differentiate, consider the following: WF With Romantic Elements ✓ Focus is on the protagonist’s emotional journey ✓ The love story only serves to kick off the emotional change (the main character changes, and that affects the romantic relationship in some way) ✓ Doesn’t necessarily follow romantic tropes or formulate or guarantee a Happily Ever After or a Happy For Now ✓ Main story events (inciting incident, climax, resolution) are tied to the outdated worldview, not to the love interest ✓ Main story question is: “Will this woman overcome some sort of internal obstacle (insecurity, distrust, people pleasing), or not?” Romance ✓ Focus is on the romantic relationship ✓ The emotional journey is in service to the love story, not the other way around (the main character must change to be with the love interest) ✓ Follows specific genre tropes and formulas (friends to lovers, enemies to lovers) ✓ Ends with a Happily Ever After or at least a Happy For Now ✓ Main story events are tied to love interest: inciting incident happens when they meet, resolution when they overcome obstacles to be together ✓ Main story question is: “Will this couple get together or not?” Target Audience Matters While women’s fiction can intersect with Literary or Historical categories, when it comes to division according to target audience, there can be no intersection. The target audience of Women’s Fiction is always adults. If your book follows a young adult character and is targeted to young adult readers, it will be classified as YA, even if it features a WF-like plot. But if it follows a protagonist’s emotional journey from youth to adulthood and is aimed at adults, it can be classified as WF. What if Your Story Has Elements of Other Genres?It's not uncommon for a book to have elements of multiple genres. Women's Fiction can include elements of Suspense, Thriller, or Romance. It’s also conceivable to put a women’s fiction plot focused on an emotional journey in a Sci-Fi or Fantasy setting, or to incorporate Magical Realism into the story. The key is determining which genre drives the story forward — what’s most prominent. If the emotional journey is the heart of the story, it’s WF. Examples:

In cases of overlap, ask yourself: what is your readership base? Are your readers drawn by the WF plot and accepting the genre elements, or are they drawn by the other genre elements (e.g., Fantasy worldbuilding) and accepting the women’s fiction plot? For example, in Avatar, while the protagonist undergoes an emotional journey—and quite a substantial one that’s central to the story. Still, the main draw is the Sci-Fi worldbuilding, so it’s considered Sci-Fi, not women’s fiction. Combining Genres When a book is labeled as more than one genre (in a broad sense of the word), the rule of thumb is to leave out implied labels.

Where Your Story Truly BelongsYou are writing Women’s Fiction if your plot revolves around your character’s emotional journey, whether or not your book is set in a historical or fantastical setting, has romantic or thriller elements, or is written in a literary style. If your novel contains multiple genre elements, you first have to determine the main genre by plot, then identify which is most prevalent. There’s some leeway in how you label your book—for example, you might highlight a magical realism element to one audience, and WF elements to another—so long as you’re realistic and truthful about what your book really is.

Your next chapter starts here. Join WFWA and connect with writers who share your passion for women’s stories.

|